|

Longest Day - Central Jersey Bicycle Club - June 2012 |

||||||||||

|

Good writing features a tight story line. Unfortunately for good writing, a ride of more than 200 miles plus the planning that preceded it fails to lend itself to such a feature. I beg advance forgiveness. The Route The Longest Day began for Marc Cecere and me with his months-ago quest to find a double century in our neck of the New England woods. The closest he managed was New Jersey. All of New Jersey. From just across the state line in Port Jervis NY, the Longest Day route more or less bisects the Garden State from north to south before reaching its terminal point 208 miles down the road at the Cape May Lighthouse. The route appealed to me, and not just for its ability to offer me my first double century. You see, climbing caps Marc's many cycling strengths. And as the profile below shows, after some early rollers, this route was tailor-made to neutralize that uber-strength of his. As it would turn out, though, I'd need something more. But that something was still miles up the road.

|

|||||||||

|

The Weather

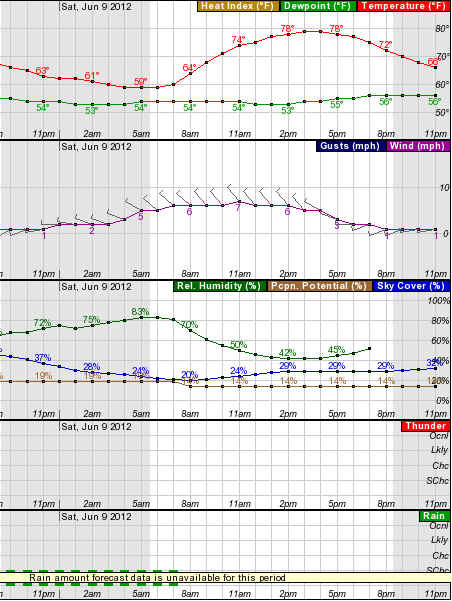

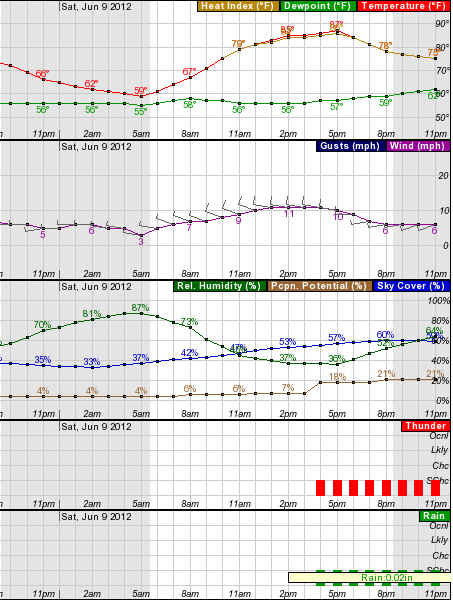

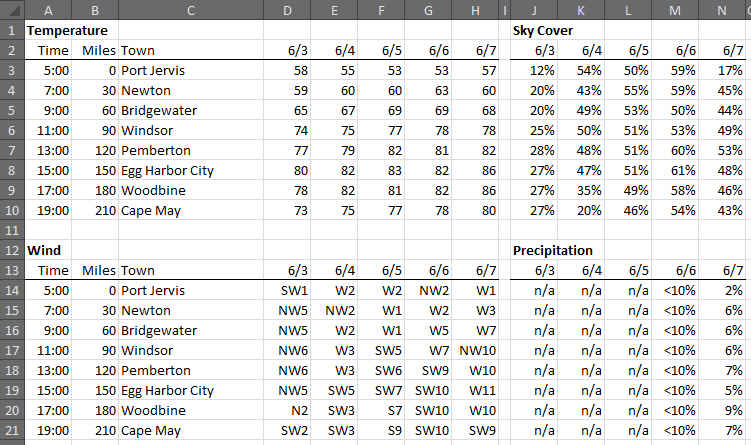

The 2012 Longest Day ride, expertly organized by the Central Jersey Bicycle Club's Neil Cherry, marked its 31st running. As with any long ride, considerations of weather quickly came to the fore. Specifically, three aspects of weather: heat, thunderstorms, and wind. Starting the Sunday before the ride, I began making daily visits to my favorite weather site, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) weather.gov. And what I saw, I liked. As it would turn out, none of the three weather concerns materialized. Tracking weather for a long ride, particularly one that's point-to-point and nearly straight, raises the challenge of needing to know not just how the weather will vary over the course of the day, but also over the length of the course. I decided to estimate the towns we'd reach every two or so hours and then launched and kept open throughout the week a browser window showing the hourly weather graph for each of those town (8 in all). Each day, I'd check and record in a spreadsheet the forecasted temperature, wind, sky cover, and precipitation for each of the eight locations and times. Yes, "alive and well" continues to aptly describe my tendencies toward OCD.

Route? Check. Weather? Check. Now all we had to do was get to the starting line. That's where my sister, Laura, came in. Her SAG support took what would have been a logistical fluster-cluck and gave us instead a manageable task. She's a saint, that Laura. The Cause Before I get to Laura, the story merits a bit of background. I first encountered the Fat Cyclist blog while riding the Triple Bypass in Colorado in 2009. The jersey of a fellow rider proclaimed "Fat Cyclist," an assertion manifestly untrue in that case. A bit of chatting and I learned about the blog behind the jersey, and the man behind the blog, Elden Nelson. "Fatty," as Elden is known to his fans, started blogging about cycling to help with his effort to lose weight. And while he succeeded, he got a lot more than he bargained for along the way. As Fatty described it, "You see, my late wife, Susan, fought breast cancer for nearly five years. She fought with focus, courage, kindness, creativity, and outrageous endurance." Susan passed away in 2009, just after I started reading his blog. Fast forward to 2012 and the 5th edition of "100 Miles of Nowhere".

During the weeks leading up to the Longest Day, an epiphany hit me (and inspired perhaps the quote of the year): I failed to register for the 100 MoN before its 500 slots filled, but by virtue of besting Fatty in a group weight loss contest back in March and April, I earned entry and the coveted swag box (whose contents, curiously enough, arrived instead in a bag) described in the 100 MoN blog post referenced above. Camp Kasem struck me as an excellent cause. And it reminded me of my sister's work as a nurse in pediatric oncology. It dawned on me that I should dedicate my Longest Day to that work. And in order to do that, I needed to learn a bit more about it. So I reached out to her husband Alex for the names of a few former colleagues of hers. I'll let their words do the talking.

The Logistics In the week prior to the ride, we pieced together a list of riders planning the full double century (the ride also featured double metric and standard century routes). My count totaled 40+; we later learned that on the order of 75 had registered. A loose consensus emerged around a 4am parking lot meeting time for riders (solo and small group) who might wish to band together. Marc and I met at the Home Depot in Natick MA and loaded his bike and gear into my Toyota Sienna minivan. Taking both cars, we headed west on the Mass Pike and made our way to Laura's place in Madison NJ. After a short visit, we left Marc's car and trekked north in mine through rush hour traffic to the Days Inn in Port Jervis NY. We checked in and headed to a nearby pizza place for some profoundly welcome carbo-loading. (The chart below documents my close-but-no-cigar attempt to get to 160 pounds in time for the ride, with red lines indicating Saturday/Sunday/Monday weighings. Ironically, my major mid-April "regression" coincided with carbo-loading during Fatty's visit to Boston for the Marathon.)  Back at the hotel, we prepped our bikes, popped an Ambien at 7:30pm, and were fast asleep before the next hour struck. By way of prep, the photos below (click to enlarge) lay out our available resources and what we'd be taking along for the ride. If all went well, the rest of the weekend would play out as follows. We'd roll out early (undertatement alert) Saturday morning toward a River Road Park SAG meeting with Laura and her copilot Lucas at the 58 mile mark just north of Bridgewater NJ. After fortifying and resupplying us, they would head on to Cape May for beach time, minigolf, and a visit with a former Brandywine High School (Wilmington DE) teacher. They would meet us at Cape May Lighthouse to ferry us back to the hotel for a shower before dinner and a well-earned sleep at the Regal Plaza in Wildwood Crest NJ. On Sunday, the four of us would drive back to Madison together. Marc and I would pick up his car (a cursed Prius, as it happened--deeper in this story, you'll learn why the dislike), somehow fit both bikes in, continue on to Port Jervis for my car, and drive the final leg back to Massachusetts. That's more or less how events unfolded. We opted to return from Cape May to Madison late Saturday night, then headed out to Port Jervis early Sunday morning, such that we made our Massachusetts "landfall" by midday. And that leaves only the account of the ride itself to relate (that's right, I haven't forgotten about the ride). The Ride  Our Ambien-fueled seven and a half hours of sleep offset the early 3:30am hour.

That, and the adrenalized energy that accompanies all "event" rides.

We made last minute preparations and headed for the parking lot to join on the order of 20 or so cyclists representing 4-5 groups.

One band of three departed a few minutes before Marc and I rolled out at 4:12am.

After entering NJ at 4:18am, we caught them a mile or so up the road as they waited for their SAG driver and then set out together.

A round of rolling re-introductions (we'd met them the evening before as they were checking int) and we knew the names of our new friends:

Ken, Steve, Dave, and their SAG driver Helen.

A good group, to be sure, and not just for the welcome headlight Dave sported on his recumbent.

Able to see holes and bumps we'd otherwise have found by Braille, we safely transited dark to dawn to day.

Our Ambien-fueled seven and a half hours of sleep offset the early 3:30am hour.

That, and the adrenalized energy that accompanies all "event" rides.

We made last minute preparations and headed for the parking lot to join on the order of 20 or so cyclists representing 4-5 groups.

One band of three departed a few minutes before Marc and I rolled out at 4:12am.

After entering NJ at 4:18am, we caught them a mile or so up the road as they waited for their SAG driver and then set out together.

A round of rolling re-introductions (we'd met them the evening before as they were checking int) and we knew the names of our new friends:

Ken, Steve, Dave, and their SAG driver Helen.

A good group, to be sure, and not just for the welcome headlight Dave sported on his recumbent.

Able to see holes and bumps we'd otherwise have found by Braille, we safely transited dark to dawn to day.

A group of two and their SAG passed us, then a group of four.

We yo-yo'd with the latter until reaching the Andover Diner at the 32 mile mark, having been passed by the Ed Hein group of 8 and their SAG just before this planned stop.

After a 15 minute break, Marc and I took a pass on breakfast and pushed on alone.

Just before the advertised but overexaggerated construction zone, we passed two riders, one of whom I think was Mike.

The rougher than average pavement did give rise to a new paceline "call" (along the lines of "car up!" and "hole!"): "gap!"

One uses "gap!" to indicate a stretch too dicy to call out individual features and instruct riders behind to create gaps and look out for themselves.

At 37 miles, we passed another 3 riders (2 men and a woman) who later joined up with a second woman and with whom we see-sawed the entire rest of the ride.

Somewhere within the first 50 miles, after a fairly long stretch of flats and descents, I queried when the road ticked up,

"What do you call it again when you have to push hard on the pedals but you still don't go very fast?"

Marc opted not to give the obvious answer of "hill" and instead said, "Age."

A group of two and their SAG passed us, then a group of four.

We yo-yo'd with the latter until reaching the Andover Diner at the 32 mile mark, having been passed by the Ed Hein group of 8 and their SAG just before this planned stop.

After a 15 minute break, Marc and I took a pass on breakfast and pushed on alone.

Just before the advertised but overexaggerated construction zone, we passed two riders, one of whom I think was Mike.

The rougher than average pavement did give rise to a new paceline "call" (along the lines of "car up!" and "hole!"): "gap!"

One uses "gap!" to indicate a stretch too dicy to call out individual features and instruct riders behind to create gaps and look out for themselves.

At 37 miles, we passed another 3 riders (2 men and a woman) who later joined up with a second woman and with whom we see-sawed the entire rest of the ride.

Somewhere within the first 50 miles, after a fairly long stretch of flats and descents, I queried when the road ticked up,

"What do you call it again when you have to push hard on the pedals but you still don't go very fast?"

Marc opted not to give the obvious answer of "hill" and instead said, "Age."

By 48 miles, the last of the ride's climbs slid into our rearview mirrors.

A ten mile descent brought us to River Road Park and our awaiting SAG team of Laura and Lucas.

Along the way, at 53 miles, we noted a cumulative average of 17.1 mph, a number we'd find ourselves all too familiar with the rest of the way.

The SAG stop allowed a change of shorts and socks, a shedding of cooler weather gear, a natural break, bananas, and best of all, peanut butter and Nutella.

In a rush to get back on the road, I neglected to fill my nearly empty water bottles, an error not penalized in the northern part of the most developed (from a real estate perspective) state in the nation.

By 48 miles, the last of the ride's climbs slid into our rearview mirrors.

A ten mile descent brought us to River Road Park and our awaiting SAG team of Laura and Lucas.

Along the way, at 53 miles, we noted a cumulative average of 17.1 mph, a number we'd find ourselves all too familiar with the rest of the way.

The SAG stop allowed a change of shorts and socks, a shedding of cooler weather gear, a natural break, bananas, and best of all, peanut butter and Nutella.

In a rush to get back on the road, I neglected to fill my nearly empty water bottles, an error not penalized in the northern part of the most developed (from a real estate perspective) state in the nation.

At the 71 mile mark around 9:00am, our average had increased to 17.4 mph. At this point, we realized that the list of bike shops that Marc had compiled in the event that we suffered was going to end up being fairly useless. With one third of the route already under our wheels, we still had another hour to go before shops would typically open, and most were in the more populous northern part of the state ... that we were getting close to leaving.  At 75 miles or so, Marc's Garmin departed from my printed cue sheet.

We followed the Garmin for a bit until we realized that it was no longer tracking propertly--we were on the west side of the Millstone River when we should have been on the east.

We took the next opportunity to correct ourselves and quickly got back on route.

Apparently, the used Garmin unit that Marc picked up for a good price may have had such a price because its endurance didn't match that of its original owner.

Starting at the 75 mile mark, rather than overlay the line on roads, it chose to display the "as the crow flies" route.

At 75 miles or so, Marc's Garmin departed from my printed cue sheet.

We followed the Garmin for a bit until we realized that it was no longer tracking propertly--we were on the west side of the Millstone River when we should have been on the east.

We took the next opportunity to correct ourselves and quickly got back on route.

Apparently, the used Garmin unit that Marc picked up for a good price may have had such a price because its endurance didn't match that of its original owner.

Starting at the 75 mile mark, rather than overlay the line on roads, it chose to display the "as the crow flies" route.

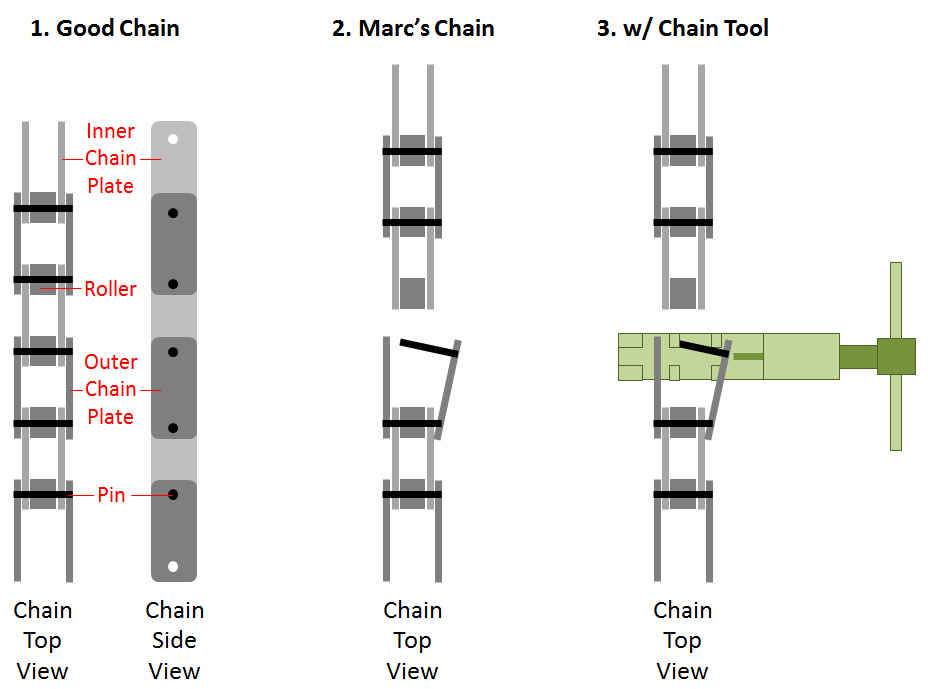

With 94 miles gone, our average had dropped a tick to 17.3 mph. Around this point, we met David and Tom from Mahway--they kindly offered us some water at a stop their SAG car had established for them in the parking lot of a convenience store. A few miles on at the 105 mile point, we began the ascent of the "Col du Chesterfield." At the time, it seemed that it had a bit of bite to it, but a careful look at the profile and the absence of even a bump suggests that we'd simply been spoiled by miles of flats. Despite having the "Col" behind us, the excitement wasn't. As the 109th mile disappeared beneath our tires, Marc called out that he'd dropped his chain. This easiest of mechanicals may sometimes be fixed by a timely upshift on the front derailleur coupled with a slow/low tension pedal, but this trick failed. Stopping to take a closer look, we encountered a double kink in the chain which we removed after a minute or two of fiddling. As Marc started pedaling again, however, he found something to be stuck. A closer inspection revealed that one of the pins had separated from the chain plates (links) such that the chain would no longer flow through the derailleur, and such that it quickly came apart. No problem! I've long carried a chain tool in my "long distance" saddle bag. Better yet, just the Wednesday before the ride, I'd gone to my local bike shop (Landry's) to ask (a) what parts I'd need to repair a chain on the road and (b) how to use the chain tool to do so. Jeremy handed me two spare pins and explained the workings of the tool. My intent was to remove the pin from the bad link, compress the bent-out bad link back in line, then push one of the spare pins back in to effect the repair. In applying the tool, however, our good fortune turned to bad as the pin on the tool sheared as I attempted to use it to push out the chain pin in the defective link. The lesson? The direction of the pin on the chain tool MUST match that of the pin you're trying to remove--otherwise, the off-center force will be too great and the tool will break. The figure below shows a functioning chain on the left, Marc's chain in the middle, and my attempt to apply the tool on the right. The photo below the figure compares a working chain tool on the right with the broken one on the left.   The situation now presented us with a problem. Our first thought was to wait for Helen, the SAG driver (for Ken, Dave, and Paul) whom we'd seen several times on the road, and throw ourselves on her mercy for a ride to the nearest bike shop on the order of 10 miles away. Our second thought was to ask the next group of riders who came along if they had a chain tool we could borrow--at the time, I didn't yet realize that my tool broke because of misapplication rather than defect. Five minutes passed before we heard the sound of bicycles coming around the bend. In typical cyclist Good Samaritan fashion, they asked if we were okay. Our plea for a chain tool brought their peleton of 15 or so to a sketchy but ultimately safe emergency halt. One of the Major Taylor Cycling Club of New Jersey riders quickly produced a chain tool from his jersey pocket and I went (carefully) to work. Seeing that the pin on his tool was starting to bend dangerously, I shifted to plan B. Rather than fix the defective link, I opted to shorten the chain by one outer/inner section. The upside of this decision? The chain tool aligned with the chain pin worked to remove the old pin. After reconnecting the chain, I applied the tool to insert the new pin. We borrowed a set of pliers from the owner of the driveway on which we had stopped and completed the repair by snapping off the "sacrificial" tip of the new pin and we were back in business. The Major Taylor group rocks, and not just because one of their members rides with a chain tool! A bit of background on Major Taylor is in order. As his bio on the MTCCNJ web site details, he boasted an impressive cycling resume that includes winning the one-mile track cycling world championship in 1899. "Taylor was the first African-American athlete to achieve the level of world champion and only the second black man to win a world championship-after Canadian boxer George Dixon." As the MTCCNJ photo gallery attests, the club is by far the most racially integrated of any that I've encountered in my many miles on the road.  The downside, you ask?

Once underway, Marc discovered that he could only access one gear combination:

the small 34 tooth chain ring on his compact crank in the front and the second smallest gear (likely a 12 or 13) on the cassette in the back.

Any higher gear caused the chain to skip unacceptably.

So, Marc pedaled the rest of the ride--a full century, mind you!--at an unnaturally high cadence for anyone not named Lance Armstrong.

Amazingly, Marc managed speeds in the 17-19mph range, but any faster and he reported that he felt like the Road Runner spinning his legs before getting traction.

Ultegra shifters, crank, cassette, and derailleurs on a single speed struck me as being somewhat unnecessary, but there's no explaining Marc sometimes. The downside, you ask?

Once underway, Marc discovered that he could only access one gear combination:

the small 34 tooth chain ring on his compact crank in the front and the second smallest gear (likely a 12 or 13) on the cassette in the back.

Any higher gear caused the chain to skip unacceptably.

So, Marc pedaled the rest of the ride--a full century, mind you!--at an unnaturally high cadence for anyone not named Lance Armstrong.

Amazingly, Marc managed speeds in the 17-19mph range, but any faster and he reported that he felt like the Road Runner spinning his legs before getting traction.

Ultegra shifters, crank, cassette, and derailleurs on a single speed struck me as being somewhat unnecessary, but there's no explaining Marc sometimes.

At 110 miles, we joined forces with Marty and Robin for a bit. Several miles later, I noted that a tailwind was aiding our progress. I crossed my fingers in hopes of it accompanying us the rest of the way to Cape May. Note to self: next time, cross fingers harder. As we prepared to make the right turn onto Main Street/Cookstown Browns Mill Road to cut across McGuire Air Force Base/Fort Dix, a van pulled off ahead of us onto a gravel parking area on the right. Two African American men stepped out and called out, "Cape May?" As we were nearly a century away from that destination, I made the assumption that they were part of the Longest Day. I yelled back, "Yes! Major Taylor?" and received an enthusiastic "Yes!" in response. As Marc and I pedaled away, I realized that I had just racially profiled! [grin] Did I mention that the Major Taylor group rocks? We found ourselves yo-yoing with them the rest of the way, their faster average speed more or less offsetting our shorter breaks. As we passed through the military base, we saw numerous "No Tresspassing" signs guarding various bivouacs and firing ranges. Cyclists often discard "Private Property" signs in the interest of "route efficiency." Nothing like a military base--and firing ranges--to set us on the straight and narrow. I chuckled as we passed Range 14, marked "Paintball"--perhaps the safest of the tresspasses were we so inclined? At 121 miles, our average stood at 17.0 mph. We sensed ourselves at risk of falling prey to Xeno's Paradox of Cycling Rest Stops.

We reconnected with our best bicycling friends Marty and Robin. For the unitiated, "best bicycling friends" refers to whichever group of riders you're currently with. BBFs result more or less equally from the friendly, instant-community nature of cyclists and the strength in numbers that help to ward off unsafe motorists. Shortly thereafter, Robin flatted. "You have what you need?" I asked. Hearing the affirmative, I replied, "See you up the road, then," and Marc and I departed.

134 miles in, our average stood at 17.0 mph. For a while, we rode with Fabian and Albert, but parted ways somewhere before the 148 mile mark. For many in New England, the number 148 resonates as it's the distance of the Harpoon Brewery to Brewery ride (2011, 2012) and in many cases--Marc's and mine included--an area rider's longest effort. Our bike computers clicked over to 149 and uncharted territory was ours. To be safe, we stopped and had lunch.  The cue sheet indicated "Little Blue House" as a food stop at the 150 mile mark, and the cue sheet delivered.

I filled up with a BLT and a Mountain Dew while Marc chose more sensibly--I also pocketed an alleged alligator meat slim jim for later sustenance.

I may still have it.

We took advantage of the picnic table on the back deck and let at least a bit of the fatigue ease away.

As we finished, the Major Taylor group stormed on by and we set out after them, not really expecting to catch them.

The drawbridge over the Mullica River had other ideas, however, and we soon caught up to them.

The cue sheet indicated "Little Blue House" as a food stop at the 150 mile mark, and the cue sheet delivered.

I filled up with a BLT and a Mountain Dew while Marc chose more sensibly--I also pocketed an alleged alligator meat slim jim for later sustenance.

I may still have it.

We took advantage of the picnic table on the back deck and let at least a bit of the fatigue ease away.

As we finished, the Major Taylor group stormed on by and we set out after them, not really expecting to catch them.

The drawbridge over the Mullica River had other ideas, however, and we soon caught up to them.

As we passed 154 miles, our average read 17.1 mph. We expected that to begin to drop, however, as we now faced a moderate headwind directly from the south. At the 168 mile mark, we again found ourselves riding with the Major Taylor group. That wouldn't last. Ahead, I noticed a parked van on the shoulder and a person lying in the grass on the far side. It took a few seconds, but I figured out that they were photographers. One of the MTCCNJ riders diverted just a bit too much of his attention toward the paparazzi. He struck a relatively deep hole and promptly pinch-flatted (I hope he at least said "cheese"), bringing the entire group to a halt. Well, entire group if you exclude Marc and me. After the obligatory "You okay? Great! See you up the road," we continued on. Best bicycle friends indeed. At both the 172 and 174 mile marks, a van bearing the words "Alpine Limo Service" pulled off on the shoulder ahead of us and waited for us to pass. I can only imagine my reaction had the driver offered a pitcher of margaritas. I'm fairly certain, however, that my longest ride wouldn now stand at 172 or 174 miles. In between the two temptations, at 173 miles, our average remained at 17.1 mph. Longest Day? How about Longest Writeup? *I'M* getting weary of writing, I can only imagine how you're doing with the reading. Hello? Hello? At 175 miles, Yancy, Ray, and Robin (and perhaps a 4th rider) moved past us. We enjoyed riding in the late afternoon sun, the light's low angle bathing us in alternating brightness and shadow. With 181 miles in the book, our average registered 17.0 mph. The longest leg on the cue sheet showed 12.1 miles, on 206 early in the ride. Many of the cues consisted, however, of "S" for straight or "X" for cross (as in, "cross Halsey Rd"), a practice that's genius both for providing additional information and breaking up what would be much longer legs. The actual longest leg that my study of the cue sheet revealed was 16.7 miles on Route 206 beginning at around 42 miles. I'm not sure why, but I prefer seeing a route with many shorter stretches rather than fewer longer ones. 191.7 miles complete, average 17.1 mph. At this point on the ride, butt soreness had been a constant companion for more than 50 miles. Rest stops seemed to cure hot spots and constricted circulation affecting feet, but not butt soreness. Unlike a ride with lots of climbing and descending, the constant flats caused constant form on the bike, and therefore little change in that most constant of human-bicycle interfaces. We wondered about the wisdom of trading saddle but opted to leave sore enough alone. It took until 195 miles under the wheels for me to figure out that I could shift to my biggest gear and stand for a while. I only did this while Marc was leading, not wanting to rub in his face his gear-limited inability to do the same. At 200 miles, our average stood at ... wait for it ... 17.1 mph. The double century mark under our belts, we had only to complete the ride. This seemingly simple task would turn out to be harder than we thought. At 205 miles in, we climbed the Seashore Road bridge over the Cape May Canal, Marc leading. As we descended, I noted a road ahead entering from the right. A car passed me on my left, then started to make the right turn. Back in April, while riding the Boston Marathon route in advance of the race, carelessness on my part ended with my being hit by a Prius. Prepared this time, and hyper alert against the "right hook," I started yelling "No No No!" at the top of my lungs while turning sharply to the right. I didn't know what lay in that direction, but whatever it was, I was going to take my chances to avoid sheet metal. The car halted its turn and came to a stop partway into the intersection. I pulled up to the passenger door and unleashed a torrent of profanity-free but no less angry protestations. "Are you crazy?! What were you doing?! What were you thinking?! Do you know you could kill a cyclist doing that?! What could possibly be so important that you couldn't wait another 5 seconds to get there?!" Right Hook 2: This Time It's Personal Eventually, the woman in the passenger seat lowered her window. I continued my tirade for another 30 seconds before pausing to catch my breath. The woman mumbled a sheepish "sorry," then said nothing more. The driver never uttered a word. Beginning to calm, I hopped back on my bike and rolled away. Marc waited on the far side of the intersection. "Did what I think happened just happen?" he asked. "Yes," I replied, then briefly recounted the sequence of events. With only 4 miles to go, we set out again. A minute later, I glanced at my rearview mirror to see Marc just a speck in the distance. His single gear proved no match for my adrenaline-fueled energy. I slowed and we quickly reformed our two-rider paceline. We weren't out of the woods yet. As we prepared to make the right turn onto Sunset Boulevard in West Cape May, a red pickup truck on the right started to pull out of a parking lot, the driver looking the other way. A loud "No!" stopped him in his tracks. After making the right, we found ourselves squinting into the setting sun as we started the last 1.7 miles before the final turn toward the Cape May Lighthouse. A golf cart swung out of a driveway on our right and headed right for us on the (for him) wrong side of the road. We edged into heavyish traffic to make our way around him, shaking our heads in disbelief. We dodged one final threat as a car pulled too far out from a side street, partially blocking our way.  We took the left onto Light House Ave and saw the lighthouse itself come into view.

Pulling into the parking lot, we found Laura and Lucas video recording our arrival for posterity.

We both had our first double centuries, and Marc had his first single speed century.

That's badass.

In the light of the setting sun, the Cape May Lighthouse would have been beautiful enough.

With 209 miles behind us, its beauty was that much better.

We took the left onto Light House Ave and saw the lighthouse itself come into view.

Pulling into the parking lot, we found Laura and Lucas video recording our arrival for posterity.

We both had our first double centuries, and Marc had his first single speed century.

That's badass.

In the light of the setting sun, the Cape May Lighthouse would have been beautiful enough.

With 209 miles behind us, its beauty was that much better.

The Numbers |

||||||||||